Robert Sparks Walker

Voice of a Naturalist: Life Lessons from the Writings of Robert Sparks Walker

Robert Sparks Walker was born on February 4th, 1878. Five months later, he and his family packed up their wagon and moved from White House, Tennessee to Chattanooga. They took up residence in a small wooden cabin built by Spring Frog (Too-an-tuh), a Cherokee naturalist from the previous century, and began to farm the surrounding 100 acres of land. In the Chickamauga Creek that ran through his family’s property, Robert learned to appreciate all of the flora and fauna that he encountered. In 1902, he became in the editor of the popular magazine, The Southern Fruit Grower, and would hold that position for 21 years. Walker wrote and published thousands of newspaper articles and poems, as well as several books. His documentation of historical records and information from the Brainerd Mission, entitled Torchlights to the Cherokee: The Brainerd Mission, was nominated for the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for History in 1931. Walker also had a regular radio broadcast and maintained a weekly column in the Chattanooga Times. During the hectic times of World War II, he recognized a need for a sanctuary for area wildlife and somewhere for increasingly urban Chattanoogans reconnect with their natural surroundings. So Walker, along with some of his dearest friends, created the Chattanooga Audubon Society and turned his childhood home and the surrounding 100 acres of farmland into a sanctuary for wildlife in the Chattanooga area.

Fifty-eight years after his passing, Robert Sparks Walker maintains an important place in the history of Chattanooga and the Tennessee Valley for his literary and journalist works caused people living in the Industrial Age to regain an appreciation of the pastoral world surrounding them, as well as learn something from it. Not only was his writing relevant then, but it also speaks to this generation of people, who are overwhelmed with technology and screens. By reading Robert Sparks Walker’s poetry and newspaper articles, one has a view of the world through the eyes of a naturalist and all the lessons it can teach. Chattanooga’s environmentalism is not new to the 21st century. Our methods may have changed, but our goal is the same as it was almost 100 years ago. Robert Sparks Walker is a perfect example of 20th-century naturalism and should be recognized for his environmental efforts that are still in service to the current day.

This exhibit is but a small view into the multi-faceted life of Robert Sparks Walker, presenting personal correspondence, photographs, as well as original poetry and manuscripts that exemplify the effect of his naturalist beliefs upon his writings and community.

Robert Sparks Walker passed on his love of nature to everyone who encountered his writing.

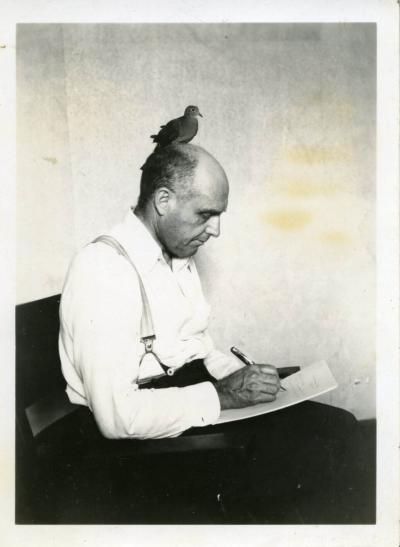

From an early age, Robert Sparks Walker nurtured an adamant love of nature. He grew up on a 100-acre farm on the eastern side of Chattanooga (now called East Brainerd), through which flowed the Chickamauga Creek. He developed an interest in plants and animals that followed him throughout his entire life. As he began writing for publications both local and nationwide, this innate curiosity seeped into the subjects of his writings. His writings reflected his awe and wonder for the natural world. He wrote on other historical subjects, like his Pulitzer-nominated book, Torchlights to the Cherokees: The Brainerd Mission, but his subjects always involved nature in some way. In this picture, the natural and literary worlds combine to show this fusion of his two passions. When he founded the Chattanooga Audubon Society in 1943, his main goal was to create a safe haven for the wildlife in the Scenic City to live in peace. So, with help from the organization, he turned his childhood home and farm into the Elise Chapin Wildlife Sanctuary, now known as Audubon Acres. Naturalism was, at least for Robert Sparks Walker, simply a way of life. His works reflected that sentiment and people in Chattanooga, the Southeast, and even nationwide grew to respect this man’s authority on insects, birds, trees, plants, and all living things. Therefore, the Scenic City has him to thank, in part, for our environmental awareness. In the following selected texts, the pure joy that Robert Sparks Walker found in nature is translated into a lesson for readers of all generations to take time to appreciate the natural beauty of our surroundings and to continue our roles as stewards of our planet and all its inhabitants.

“... and he made me blush when he said, “I am so glad you came into my life when you did.” I have been so much happier and have had my years enriched by his friendship - and Chattanooga has been made a more interesting and better place for me to live x I wonder how I can ever repay you? - I told him frankly I had had one of the most interesting days of my life and I felt the same about his friendship…”

Entry from Robert Spark's Walkers diary, page 349, Wednesday, October 31st, 1945

This excerpt from one of the dozens of personal diaries contained in the Robert Sparks Walker collection. Specifically, this entry details Mr. Walker’s feelings about the events of this very special day. On October 31st, 1945, the Chattanooga Audubon Society held a tree dedication ceremony for the benefactor of the sanctuary, E. Y. Chapin. This was an important day for Walker because he had been working for over two years for this very day. After he created the Chattanooga Audubon Society on July 2nd, 1944, their main goal was to purchase the Walker farm and convert it into a wildlife sanctuary. At first, it looked hopeless because they were unable to raise the $6,000 needed to purchase the property from the six heirs (a specially discounted price for this noble cause). However, Mr. Walker ’s vision was realized because of his longtime friend, E. Y. Chapin. This gentleman bought the Walker farm outright and immediately handed it over to the Chattanooga Audubon Society so that they may achieve their goal. Here, Mr. Walker talks about a personal conversation they had had during the dedication ceremony. One can easily detect the gratitude in his words as he documents the day’s events. He asks how he could ever repay his friend for such a selfless act. Robert Sparks Walker remained humble, even as he became a local celebrity for his environmental efforts in Chattanooga. This is evident in the fact that he said he blushed when Mr. Chapin told him that he was glad they were friends. Robert Sparks Walker’s legacy lives on at his father’s farm. Audubon Acres continues to fascinate visitors from all around the region through its trails and informative plaques detailing the species of almost every plant on the property. Audubon Acres remains a safe haven for area wildlife and a retreat from the industrial and digital world surrounding it.

Walker’s reverence for the natural world is best portrayed through his writing.

“I cannot help from thinking that it is all for the express purpose of coming to the rescue of the thousands of people in the city who without association of her wild creations would leave this old world with a partially developed mind and soul! I have never seen Nature fail in coming to the rescue of every living thing and doing for it that which it can not do for itself.”

Walker, Robert Sparks. "Talks With A Naturalist: Flower Of Course!." 1927. Chattanooga, Tennessee.

In this newspaper article, one of the thousands that he penned over his lifetime for the Chattanooga Times and many other prominent magazines, Robert Sparks Walker talks of his admiration of the personified Mother Nature. He equates her to a benevolent friend who is always concerned for her human counterparts and believes her to be absolutely essential to our spiritual and mental wellbeing. He lived his life as if he and nature were the best of friends, showing curiosity and kindness for all living things he encountered, humans included. Nature is our protector, our benefactor, and our friend and wants to pull us from our asphalt jungles not only for our health but also our spiritual rejuvenation. It was this belief that he carried with him all of his days on this earth and it was this belief that he instilled in every friend and family member so that his enthusiasm for preserving the pastoral aspect of our region has trickled down into our current generation. Citizens of the Scenic have the opportunity to reap the benefits of Nature’s friendship by simply changing their mindsets from considering nature as a nuisance to seeing it as an ecosystem that holds the most precious commodity: life.

SPRING FROG: Cherokee Naturalist

Did you learn kindness from the birds,

You with meek spirit, clean and pure?

And did their songs enrich your words

With truth’s ambition to secure

A peace and friendship with all men?

Did glimpse of tree and flower inspire

You to seek truth and beauty, when

They burst in bloom in zenith’s fire?

The gestures of the green tree’s limbs,

The words of Chickamauga’s flow,

The piping of pine needle hymns,

The tracks of mammals in the snow,

The croaking of the toads and frogs,

The howls of wolves in darkest wood,

The reptiles of the hills and bogs

Was language which you understood.

You found no beast which you could fear,

And no distress

Of heart and mind was yours to bear;

There was no toper in your clan;

No dread of robbers to despoil

Your happiness,

Until you met a pale-faced man --

The arch-intruder of your soil!

Walker, Robert Sparks. “The Chattanooga Audubon Society

and its Elise Chapin Wild Life Sanctuary.” no date.

The sense of reverence that Robert Sparks Walker has for a man he had never met, yet had a significant influence on his life, emanates from every letter in this poem. The author appears to be the persona or speaker in the poem. In the first stanza, Robert Sparks Walker is asking how Too-an-tuh (“Spring Frog,” as translated to English from Cherokee) lived in harmony with the Nature around him, so that Walker and others after him may follow in Spring Frog’s ways and thereby honoring him through their appreciation of the natural world. Walker is also implying that Nature is a universal language. People do not need to speak the same language to appreciate something like a beautiful sunrise. Robert Sparks Walker is calling Nature the great equalizer. If current generations can get back in touch with our pastoral surroundings, then we will find peace within ourselves and balance between us and the natural world that we inhabit. Walker’s writings demonstrate that if we humans spend more time communing with Nature (say, for instance, in a wildlife sanctuary?), we will find the harmony that comes from the peaceful balance of the self.

The Farm Incarnated

An animated lump of clay

Am I, with Thought upon the throne

Charged with a voice whose richest tone

Tells of a life of yesterday

With its delights and treasured charm,

When I was living on the farm.

At first I owned a plastic mind,

And when the storms and calms appeared,

They left their deep impressions seared;

My nature well with them combined,

And smiles and frowns were thus in me

Born to exist eternally.

Though born to love, yet hate I knew;

Sunshine each day my nature craved,

But bitterness my heart my engraved;

My body kept the records true,

In both a sad and cheerful tone,

I was a living gramophone.

My thoughts and deeds must now reflect

The floods, the storms, the trees, the hills,

The birds, the flowers, the springs, the rills,

And object lowly and erect,

For I became without consent

A product of environment.

Time’s plowshare furrows deep my cheeks,

The cares are many that he brings,

I drink the water from foul springs,

Grave error-drifts float down my creeks;

The scum of ponds is my reward.

And disappointments I record.

But flowers rich my path perfume,

My work brings gladness year by year

The songs of birds are mine to hear;

Sweet voices cheer my darkest room;

The good and bright by far outshine

The gloom and sorrows deep of mine.

A plastic mind and spirit, too,

Are films unexposed, unknown;

One season only is their own.

Mine grasped the things that round them grew:

I am the incarnation here

Of father’s farm I loved so dear!

Walker, Robert Sparks. “The Farm Incarnated.”

My Father's Farm. Boston, MA: Four Seas Press, 1927.

From this poem, written in 1927 for his second poetry anthology, My Father’s Farm, the reader is able to peer into the inner thoughts of Robert Sparks Walker, who wrote this poem when he was 31 years old. In the text, the speaker believes himself to be the personified version of his father’s farm. No matter how far away from it he moves, the persona often thinks of that peaceful piece of land that holds his most precious childhood memories.

The underlying theme of this poem is duality. Walker writes, “Sunshine each day my nature craved, / But bitterness my heart engraved.” This quote identifies that the speaker’s natural inclinations toward peace and tranquility in nature are in stark contrast to the society in which he lives. He has had many disappointments, but he endeavors to find the positive in everything. Instead of closing himself off to the world and becoming bitter from his disappointment in humanity, he becomes a medium for the moments of gladness and despair that make up the human experience.

Walker’s pride in his upbringing can be seen between the lines of this poem. The persona indicates, in so many words, that he is the humanized form of his father’s farm. It is almost as if the farm is both a good friend and his own self. The persona alludes that his father’s farm has a soul and, by his leaving his childhood home and putting down roots in another place, that he carries that soul within him along with his own. This duality of spirit creates a link between the past and present. All that he is now comes directly from his past. It is a strong image, revealing the importance of heritage and its place in the biographies of each person. It is a beautiful image with which to end a poem because Walker is implying that we all carry with us the memories of our childhood homes, so that we may never forget our origins and those memories will continue to remind us of home, no matter where that may be.

Expression of Literary Beauty in Wildflowers

“When a person goes into the garden and associates with [these] flowers, he is simply reading the most delightful poetic expressions as he looks into the face of each open blossom.”

Chattanooga Times book review July 21st, 1937, “A Garland of Poetry”

This quote truly is the essence of Robert Sparks Walker’s character. His connection with nature was the motivation for his writing. Flowers, birds, trees, and many other species were the muses that inspired his pen to create beautiful and educational works of such far-reaching acclaim. This quote is also a message to his audience. The lesson is for all people to take time to truly absorb the natural beauty surrounding us. Walker is advising readers, through all of his writing, to connect with the world around them… and not with just nature, but also with people. Making connections was Robert Sparks Walker’s entire life. His magazine connected with people nationwide. His weekly newspaper column and radio show connected his words to the young and old citizens of Chattanooga, passing on to them a little of himself. He gave each of his readers a gift: the ability to see more than just buildings and trees and grass, but life itself. Walker found poetry in flowers because he stopped and took the time to fully appreciate them. We of this era are entrusted with the same task, so that we may experience the same joy he felt with every living thing he encountered.

Robert Sparks Walker’s goal was to educate and inspire.

“It is a beautiful world, and I am so glad that early in life I learned to love many things better than money. That is what I should love to teach every child.”

This quote is taken from a letter written by Robert Sparks Walker on November 23rd, 1943. While talking about his plans to convert his family cabin and surrounding farmland into a bird sanctuary, Walker ponders his life’s purpose through these words. Instead of stating that he deserves all the credit for this idea and the creation of the Chattanooga Audubon Society, he gives all the credit to his childhood and the way he was raised by his parents. His life on the farm gave him a unique perspective on life. Instead of pushing for progress, he wanted to preserve the farm as a refuge from the industrial town growing around it. He endeavored to teach peoples of future generations the wonder of nature so that they might teach their children, and so on, thereby keeping pastoral fascination and wonder alive. The lasting impression that Robert Sparks Walker had on the Scenic City continues to live in the eyes of every child that steps off the bus at Audubon Acres and takes in the scene of a small rustic cabin surrounded by green grass and some of the most beautiful trees in the Chattanooga area. Walking along the same trails that he created and used almost every day until his passing, all visitors come away with a sense of having absorbed part of that lesson that Robert Sparks Walker wished to impart to each and every one of us.

Optimism

Yesterday I saw an oak tree dressed

In the greenest robe the woods possessed;

And the wild winds wafted through its crown,

And its acorns large were turning brown;

For so prosperous was it that day,

That lo! it had wealth to give away.

Six months later, I saw it again,

It was not the same tree-citizen;

For its wealth was gone, its body bare,

And its crown and trunk seemed shrunk with care;

And although it looked like it was dead,

Bravely it grew on with upright head.

Should I e’er be stripped of wealth or fame,

I’ll work on, and cling to my good name;

I will stand erect, and laugh and smile,

For misfortunes last the briefest while;

It is man’s own will and wrinkled frown

That can trip him up and keep him down.

From this poem, it is clear that not only was Nature the friend of Robert Sparks Walker, but it was also his teacher. Something as simple as an oak tree exemplifies humility, optimism, and perseverance, three traits that mankind needs to master and what better teacher than nature? In the first stanza, the speaker personifies the tree as royalty of the forest, with the “greenest robe,” and wearing a “crown.” This is a common allusion in Walker’s poetry and it expresses his true feelings for these majestic plants. By personifying the tree, the speaker creates an equality between himself and it. He witnesses two of its states, in the full bloom of Spring and its dormant state in Winter. From these opposing encounters, the narrator absorbs an important lesson. His perception of the first meeting with this oak tree is that its prosperity lies in its full leaves and budding acorns. From this, the persona initially believes that material possessions are what makes the tree proud. However, this could not be more untrue. The second occurrence is in stark contrast to the first. Autumn and Winter have caused the tree to become dormant in anticipation of Spring. It has lost all of its leaves and acorns, so it has nothing to give, no material possessions to share with its neighbors of the forest. Even though this scene is melancholy and desolate at first glance, the narrator sees the positivity in the tree’s willingness to live. The tree has nothing to give, yet it holds its crown high with pride and fortitude. This bravery is understood as being a continuous positivity. The tree’s endurance, regardless of the weather, imbues in the speaker the lesson that, whether in prosperity or poverty, a positive outlook on life is the best trait that a person can have. So, the narrator says that he “will stand erect, and laugh and smile,” a resolution that he also seems to be extending to the reader. In all of Robert Sparks Walker’s writing, there is a lesson that we all can learn. Regardless of our situations, we can all foster positivity to combat the bitterness created by continuous progress.

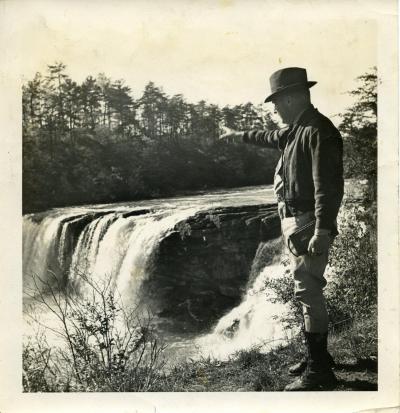

The Naturalist at Little River Falls on Lookout Mountain

No matter the circumstances or location, Walker took every opportunity to teach and inform. In this picture, Robert Sparks Walker is looking out over Little River Falls, speaking to the people present about the history of the area. He actually wrote an entire book on one mountain, entitled, Lookout: The Story of a Mountain. Once up and running, Audubon Acres became Walker’s classroom. Some of the visitors to the wildlife sanctuary while he was there (which was almost every day) would be taken on personal tours, learning about the flora and fauna sighted along the way. As he said himself, his fondest wish was to impart to others the history of Chattanooga and all that nature had taught him. Walker wanted to pass on the wisdom that he had accumulated over a lifetime so that this knowledge will be used to further his life’s mission of preserving the wildlife and plant life of the Chattanooga area, thereby allowing future generations to learn from him long after his passing. Robert Sparks Walker’s life was spent in the service of others and that is why this man has such a prominent place in the history of Chattanooga and the Tennessee Valley.

Robert Sparks Walker - final block

Sources Consulted

Clark, Alexandra Walker. Chattanooga's Robert Sparks Walker: The Unconventional Life of an East Tennessee Naturalist. Charleston, SC: Natural History Press, 2013.

Clark, Alexandra Walker. Hidden History of Chattanooga Charleston, SC: History Press, 2008.

Walker, Robert Sparks. As the Indians Left It: The Story of the Chattanooga Audubon Society and Its Elise Chapin Wildlife Sanctuary. Chattanooga: G.C. Hudson, 1955.

Walker, Robert Sparks. My Father's Farm. Boston, MA: Four Seas, 1927.

“Robert Sparks Walker - Author, Naturalist, Teacher.“ Chattanooga Audubon Society. https://www.chattanoogaaudubon.org/history.html

Credit

This exhibit was developed by Haley McCullough, an intern in Special Collections from the Department of English in Fall 2018.