Jessica Auchter

On the Cutting Edge:

Spotlighting Teaching Innovation at UTC

The Walker Center’s “On the Cutting Edge” is an occasional essay series by UTC faculty spotlighting teaching innovation across the UTC campus. Interested faculty are encouraged to explore WCTL’s Innovation Grants webpage as well as experiential learning resources through ThinkAchieve: Beyond the Classroom.

Taking Risks:

Experiential Learning at UTC

in a Global Advocacy Context

Today, we feature Dr. Jessica Auchter of the Department of Political Science and Public Service, who received a WCTL High Impact Practices Grant in Fall 2019 for her PSPS 4000 Capstone Class, which allowed students to develop their own advocacy project in collaboration with Scholars at Risk. Here, she writes about her approach to experiential learning and teaching innovation.

1. The Innovation: Advocacy Work

What motivated your teaching experiment and what specific practice did you bring to your class?

Good research has to inform traditional academic paper writing, but it also informs human rights reports and effective advocacy work. I tasked students in my PSPS Capstone Class with advocating for a specific imprisoned scholar, working alongside the non-partisan organization Scholars at Risk, who works to advocate for scholars worldwide who have been imprisoned for exercising their academic freedom or right to free speech.

The PSPS Capstone Class has a focus on independent research. While the students each developed their own independent research project that culminated in a paper on the theme of democracy, I wanted the class to be about more than just a paper as an outcome of research. In the subfields that make up Political Science and Public Service, many of our students will go on to careers that do not involve research in the traditional academic sense. As a result, it is an important goal of mine for them to consider the myriad ways research can matter, especially in the lives of human beings.

This community partner, Scholars at Risk, would be able to help us with initial information and contacts for the project. This seemed to be a realm that allowed us to consider the practical impact of democratic decline, especially in the area of free speech issues. This meant we were working with a very real case, and with one individual who is in a precarious situation and whose life we could potentially impact.

The Goals of this advocacy work were threefold: (1) to help us better understand the relationship between democracy and human rights by focusing very narrowly on one case, particularly the obstacles and constraints to effective action, thereby helping us apply course material; (2) to help us see how research is used by stakeholders and focus on a real world situation, to help the students inform their own academic research projects as well; and (3) to force us to consider what it means to study human suffering and the relationship between engaged scholarship and advocacy.

The content and scope of the advocacy project was left entirely up to the students. The students even chose the specific scholar we would be working with out of three options that had been vetted by Scholars at Risk, and we discussed as a class the potential challenges and obstacles when we made the decision. In the end, they decided on Indian Professor G. N. Saibaba, currently imprisoned in India for his human rights advocacy work with the Adivasis and other ethnic minorities, and his related criticism of the Indian government and its development projects.

The High-Impact Practices grant would fund their project, and the decisions about how the funding would be used would be up to the students, reinforcing their agency in the advocacy project. In the end, the students developed and hosted an Advocacy Week on campus at the end of October 2019. They chose the events, with my guidance, and it was their ideas that they worked hard to implement.

Dr. G.N. Saibaba, English Professor at Delhi University

2. Student Reaction and Involvement

How did your students respond to the innovation? Were they open? Was there any resistance? What improvements did you notice in their learning?

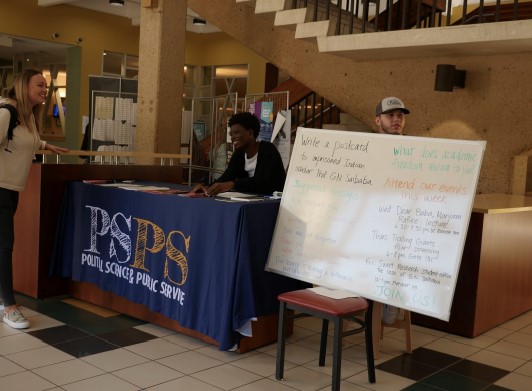

The students haven’t often been put in a position where they were in charge of the actions and outcomes in a course. They were initially tentative and concerned that they didn’t know enough to be able to engage in effective advocacy. We discussed how to develop effective expertise and embarked on a process of information gathering, including speaking to friends of Professor Saibaba and learning more about his legal case and background. During the advocacy week, students made committees that would work on various aspects. Some students tabled in the UC to get students to fill out postcards with messages of support that would be sent to Professor Saibaba in prison, and to advertise the week’s events.

PSPS 4000 students Austin Hooper, Brianna Jones, and Hayley Pirrera tabling in the UC

Others helped organize the other events, which included a film screening, a talk by a guest speaker who engaged in advocacy work for her own father, an Iranian professor who had been in prison, and a research talk by the students themselves, to share their project with the UTC campus. Other students worked on a Wikipedia page for Professor Saibaba, designed event flyers, and wrote articles in the student newspaper:

Modi and the Pipe-Dream of Bloodless Revolution

PSPS Capstone’s Advocacy Week Makes Impact on Campus and Beyond

Students also created a YouTube video reading some of his poems that could easily be shared on social media: Saibaba Video. And hey were interviewed by WUTC radio station about their work: WUTC Interview.

PSPS 4000 students Tyler Wheat and Courtney Scott with Ray Bassett, host of WUTC’s Scenic Roots

Thanks to the Walker Center for Teaching and Learning, we were able to fund postcards, stamps to mail them, the printing of advertising material for the on-campus events, and a wider campaign to get signatures on a petition on Professor Saibaba’s behalf.

In the end, despite starting out with concerns and hesitation, all the students agreed that they left with a sense of accomplishment and a more realistic sense of their own abilities and external obstacles to effective advocacy work. In other words, they learned to have confidence in their ability to apply their skills to a real-world case.

3. The Future: Continuing the Work

Will you continue using this innovation in the future? Are there any modifications that you will make?

I do plan to continue to emphasize student agency in work of this nature. It is important for us to facilitate hands-on learning for our students in ways that prepare them to feel confident in their knowledge but also in their ability to use their skills to engage in new processes and to apply their knowledge to practical endeavors.

In terms of modifications, I would advise anyone considering hands-on advocacy work in their classes to keep as small of a class size as possible. We were lucky to have 12 students, which enabled us to be able to form a well-functioning group that could be organized in our work. Additionally, ensuring that the students are committed to this work is important, so I would not incorporate advocacy work with Scholars at Risk in a mandatory course, but rather one that students can opt into based on their interest. The main reason for this is that we owe something ethically to our community partner. While student learning is the focus of any course, there is an added element when working with a community partner that entails respect for the processes and time of that partner.

Scholars at Risk’s Facebook Page recognizes the work done by UTC students in PSPS 4000

Next time I will build in more opportunities for in-class and written reflection. The students did write written reflections in their class journals, but due to the timing of our advocacy week, it was more difficult to set aside time in class to fully debrief. I would find a way to make that happen next time around.

4. Experiential Learning: Confidence and Constraints

What value do you see in experiential learning? Do you have any advice for a colleague who might be skeptical about such innovations?

Experiential learning gives students confidence in their own abilities, while also allowing them to understand the constraints of practical action. Early on in our course, students were very idealistic about what they could accomplish. I had a frank discussion with them about potential outcomes. In this case, Professor Saibaba was very ill, so it was a possibility that he could die in prison during our semester. We discussed what that meant for our work, and how we could ensure that his legacy lived on. One piece of advice I have that helped is to invite experts into our classroom: in this case, family friends of Professor Saibaba and the daughter of a formerly imprisoned Iranian scholar who advocated for her own father. Both emphasized that while release from prison would be an ideal scenario, our goal should be bigger than that: to draw attention to the case however possible and to add our small voices to an effort that is bigger and beyond our class. They emphasized thinking small: Doing one small thing well could enable someone else to pick up the work where we left off when the semester ended. This helped the students contextualize their own work and its limits.

My advice in terms of course mechanics is twofold: first, explain to students why you are doing things the way you are. Invite them into the process, don’t just give them an experiential project and let them run with it. Instead, as the facilitator of the project, focus on sharing with students the “why” and being transparent with them about the potential chaotic or unplanned parts of the process.

This leads to my second point: be transparent about grading. If you are evaluating student work for a hands-on project, how will you evaluate it? How will you measure effort? What type of reflection will come along with the project? Given that experiential projects are often in flux with unexpected processes, it is important for the faculty member to offer transparent mechanisms of evaluating students given potential changes in dates, etc.

I see experiential learning as a way of designing coursework that allows students to understand the complexities of what their course material looks like in the messy real world. Robert Cox famously said that theory is always for someone and for something. If that is the case, faculty have a responsibility to model for students what this can look like and to facilitate opportunities for students themselves to engage their own agency in the learning process.

INNOVATION OPPORTUNITIES

Teaching and Learning Grants

The Walker Center for Teaching and Learning sponsors two grant programs to encourage innovative teaching, the High-Impact Practices (HIP) Development Grant ($2,000) and new Classroom Mini-Grant ($300). Deadlines are monthly and fall generally at the first of each month.

Experiential Learning Resources

ThinkAchieve: Beyond the Classroom is the platform for supporting Experiential Learning at UTC. Faculty can learn more and apply to have their classes designated as Experiential Learning.