Conventional and Unconventional Political Participation: Democracy in Action

This complete module with all materials may be downloaded as a PDF here.

Matt Logan

LaFayette High School

LaFayette, Georgia

This module was developed and utilized for a ninth-grade advanced placement U.S. government class to teach the AP syllabus topic "Political Beliefs and Behaviors: Conventional and Unconventional Political Participation."

Estimated module length: Ninety minutes

Conventional political participation: The signing of the U.S. Constitution. Source: Teaching American History at https://tinyurl.com/ycy8r933.

Unconventional political participation: Boston Tea Party. Source: Wikipedia at https://tinyurl.com/y9g9gua5.

Overview

The United States is a democratic republic. This system of governance allows U.S. citizens to engage directly in political life through attempting to influence the public policies of their government. This allows different individuals and groups to choose various forms of action for different purposes. Conventional strategies like voting, running for office, making donations to candidates, or writing members of Congress are common and widely accepted. Unconventional participation is less widely accepted and often controversial. It involves using strategies like marching, boycotting, refusing to obey laws, or protesting in general. At different times in the nation’s history, individuals and groups have succeeded or failed using both forms of participation.

Objectives

Students will:

Explain that in a democratic republic, citizens participate in the political system through their actions that can be conventional or, at times, unconventional.

Learn the concepts of conventional and unconventional political participation and study the civil rights movement as an example of a successful use of unconventional political participation.

Better understand the categories of conventional and unconventional political participation and types of actions associated with each category through applying knowledge to three political scenarios.

Prerequisite Knowledge

In my course, this lesson is embedded in a unit on political beliefs and behaviors of U.S. citizens. It stands alone and requires no formal prerequisites, though students should have a general understanding of democracy as a form of government. It follows lessons about political beliefs and anticipates future lessons about voting and elections, civil liberties, and civil rights.

Module Introduction:

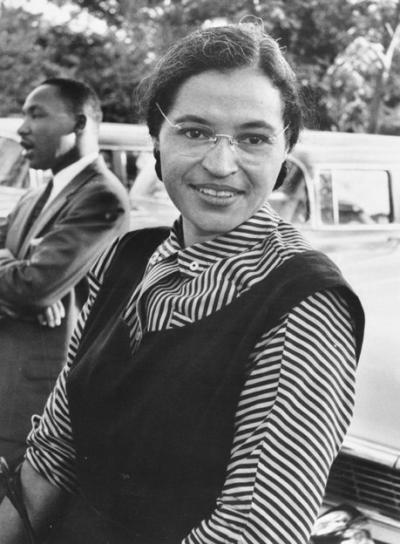

Rosa Parks with Martin Luther King Jr. in the background. Source: Wikimedia Commons at https://tinyurl.com/b4wuyon.

Students are first asked to access and read the Constitutional Rights Foundation web page titled âSocial Protestsâ at http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/social-protests. This student reading with accompanying questions is a case study of the 1950s and 1960s civil rights protest movements. The reading is available for download at this link and is also included in Appendix I of this module. If laptops arenât available, students can use their smartphones or the page can be printed and distributed. Students should read the accurate, concise, and objective overview of the protest movement and answer the two accompanying questions at the end of the reading. After completing the reading and questions, students are randomly asked to share their answers aloud. After hearing from two or three students, the teacher should then introduce the two core generalizations of the lesson by offering introductory comments similar to these:

First, although sometimes people in a democratic republic choose to participate in politics in an unconventional manner, including protesting, boycotting, and refusing to abide by certain laws, most people choose to participate conventionally, by voting, donating money to candidates for political office, or even running for office.

Second, people involved in the civil rights movement often chose the unconventional means of protest (as the students have possibly already discerned) because they were unable to have their voices heard through more conventional means, since as a racial/political minority, particularly in the South, established laws and generally accepted customs of the white majority denied African-Americans conventional access.

As students learn more about conventional and unconventional political participation, they should realize that different situations and individual and group interests mean that there is no standardized formula for choosing or not choosing actions from either or both categories that work in every situation (estimated time, forty minutes).

The Basics of Political Participation: Understanding and Applications

Students then receive the handout âConventional and Unconventional Political Participation.â The handout clarifies and specifies types of political participation, as well as provides students with scenarios that give them opportunities to apply what theyâve learned. The handout is available for download at this link and is also included in Appendix II of this module. The document breaks down political participation into two categories: (1) conventional participation including voting, donating money, writing letters, joining an interest group, and more; and (2) unconventional participation including protesting, boycotting, rioting, and more. Randomly ask students to read the categories in the handout aloud.

Students then read the three short scenarios included in the handout and imagine themselves as the individual involved in each scenario: (a student concerned about low voter turnout among young people, a business owner who battles government bureaucracy, and a citizen concerned about poor local governance). They then are asked to choose one or more of the two categories of political participation, as well as specific actions from one or more of the categories they choose, that might assist the individual in changing the problematic situation he/she encounters in each scenario. Students then write brief scenarios of their choices and why they chose to act as they did for each typeâs effectiveness.

Next, students will work in groups of four. Predetermined mixed-ability groups work well for this assignment to encourage thoughtful discussion and multiple perspectives. Each group should try to find consensus about what type of action would work best in each scenario. The groups need not produce a document, but they should formally agree upon the best course of action for each scenario. During this process, it is suggested that the teacher circulate in the classroom, checking for understanding, answering any questions that may arise, and trying to help create consensus within each group (estimated time, sixty-five minutes).

Conclusion/Summary

After all groups have shared and discussed their thoughts with each other, the teacher will take up each studentâs written responses to the individual writing assignment and then address the class and summarize comments from different groups. Students will have disagreed on many finer points, but have mostly all agreed that some types of actions were required and, further, agreed that each situation called for a different response geared specifically to each scenario. The teacher may summarize the lesson with a brief statement like the following:

As we saw, participation in the civil rights movement took extraordinary courage. Everyday citizens used what little political power they had to fight for the changes that they wanted to see. The citizens who worked with the movement sometimes behaved conventionally by voting or helping political campaigns with time or money, and sometimes they behaved unconventionally through protests, boycotts, or civil disobedience. While most political situations donât call for the level of effort the civil rights movement did, political participation is still an effective way to try to use the power that you, as a citizen, have in a democracy, whether thatâs through the most popular form of participationâvotingâor through protest and other less common methods. We may disagree about how to achieve our goals, but we can all agree that we should use our power to represent ourselves politically and that the methods we choose should not cause harm.

Day two: Reinforcement Activity/Summative Assessment

As an introduction to the next dayâs lesson concerning voting (turnout, trends, demographics, and laws/amendments that impact voting), students will be prompted to list the two general types of political participation and give two specific examples of each. The assignment will be collected and graded to assess concept attainment in students.

References and Resources

OâConnor, Karen, and Larry Sabato. American Government: Roots and Reform. 10th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Pearson, 2009. This source is a textbook that is recommended for AP U.S. government and politics classes. It provides a general overview of government.

Thorson, Esther, et al. âA Hierarchy of Political Participation Activities in Pre-Voting-Age Youth.â University of Missouri, 2010. http://www.newshare.com/mdp/mdp-participation.pdf. This paper from the University of Missouri discusses youth participation in politics. It provides teachers with useful, specific background on political participation as it relates to young people.

âVoter Turnout Demographics." United States Election Project. Last modified 2016. https://edubirdie.com/blog/voter-turnout-data. This source from the University of Floridaâs United States Election Project provides current data on turnout rates, trends in voting, and useful graphs to illustrate political participation levels.

http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/social-protests: This resource is used to introduce students to a historical example of unconventional political participation, the civil rights movement. Specific events from the time period are discussed, and students are exposed to many of the strategies that were used.

Matt Logan, âConventional and Unconventional Political Participation,â May 15, 2017.