Lincoln: The Man, the Politician, and Slavery: 1838–1858

This complete module with all materials may be downloaded as PDF here.

Jeremy Henderson

Center for Creative Arts

Chattanooga, Tennessee

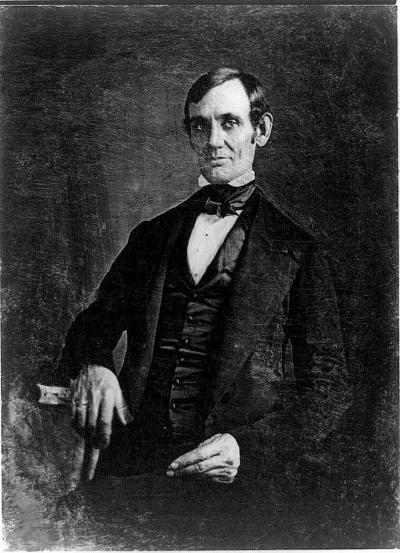

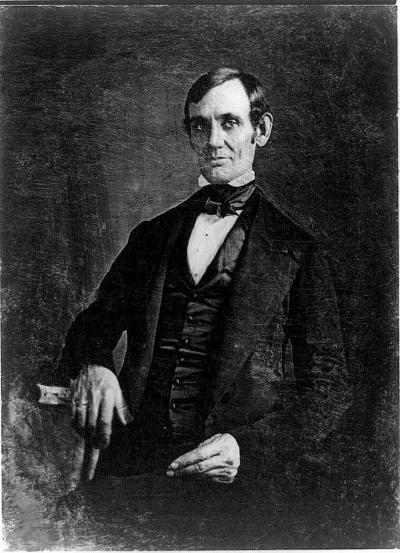

Abraham Lincoln, 1840s (left) and the Lincoln Memorial (right)

Source: Wikimedia Commons at https://tinyurl.com/y9d8z9e8 and https://tinyurl.com/ya5xpnfh.

Overview

This module was originally developed and utilized in an eighth-grade American history class in order that students might have more realistic perceptions of Abraham Lincoln as a human being and an aspiring leader, and to understand his views about slavery before the Civil War. The module can be easily adapted to high school American history courses.

Many, if not virtually all, middle and high school students have difficulty humanizing Lincoln because of a lack of knowledge about Lincoln’s life before he became one of the nation’s greatest presidents. Little or no understanding of Lincoln’s early life and his thought and writing before becoming president often causes students to easily succumb to the erroneous notion that Lincoln was an abolitionist, or the even more inaccurate perception that Lincoln cared nothing for the plight of black slaves. This module is designed to assist students in the cultivation of a more accurate and nuanced view of Lincoln, and hopefully complements existing textbooks and other pedagogical tools readers might use in their classes (estimated time, two and a half to three hours).

Objectives

Students will:

Differentiate between the somewhat dehumanized Lincoln of the Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore and Lincoln the human being—a person with arguably the most humble origins of all American presidents and the politician whose views evolved yet who consistently possessed antislavery beliefs.

Analyze primary source excerpts of Lincoln’s speeches and letters from before the Civil War to think about Lincoln as an aspiring leader and to better understand his views about slavery and how they changed.

Think about Lincoln in the context of nineteenth-century rather than early twenty-first-century beliefs about African-Americans.

Prerequisite Knowledge

No prior knowledge of Lincoln himself is necessary. Basic understanding of the following terms and concepts will be helpful: abolition movement, Africa colonization plans for former slaves, Missouri Compromise, Compromise of 1850, Fugitive Slave Law, Kansas-Nebraska Act, and Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Module Introduction: Lincoln, Stone and Fles

Steps one through three are part of introductory activities and should move quickly relative to the remainder of the module.

Warmup, part one (estimated time, fifteen minutes)

Source: Wikimedia Commons at http://tinyurl.com/y74mhpco.

Show photo of Lincoln Memorial on-screen or provide printouts for each group. Have students answer the following questions either individually, in groups, or as a whole-group discussion:

What words or phrases come to mind when you see this image of Lincoln? What are the first thoughts for you personally when you hear someone mention Lincoln?

What sort of mood does the Lincoln Memorial convey?

What can we learn from visiting memorials for famous Americans?

What information might we lack by learning about famous Americans only through memorials and statues?

How might a memorial be a misleading representation of a historic figure? (During discussion portion, the teacher may want to talk about the debate that occurred over the Lincoln Memorial when it was conceptualized and constructed. See resources for more information.)

Warmup, part two (estimated time, five to eight minutes)

Source: Wikimedia Commons at http://tinyurl.com/y86ncut3.

Show the 1846 daguerreotype of a young Lincoln on-screen.

An earlier photo of Lincoln was chosen for this lesson intentionally, as most students are familiar with photos with from his presidency. Have students answer the following questions either individually, in groups, or as a whole-group discussion:

What words come to mind about Lincoln as an individual when you view this photograph? (Students should be informed that because photography had just been invented and being photographed was considered a significant experience, few people in the nineteenth century smiled in photographs. Also, holding a smile for the lengthy exposure time was difficult.)

What does this photo show about Lincoln’s personality?

Why might a photo give us a better starting point of discussion about a person than a statue?

Lincoln’s early life: Video and discussion (estimated time, ten minutes)

"Lincoln: Growing up on the Frontier"

Show the three-minute video from "Lincoln: Growing up on the Frontier" about Lincoln’s early life (https://youtu.be/rXdZe1Q-dQo).

After the video, have students write two or three sentences describing any surprising or unknown facts about Lincoln’s early life they learned, and lead a brief class discussion based upon student responses.

Document analysis (estimated time, one and a half hours for both steps four and five)

Students will analyze excerpts from Lincoln’s speeches that focus on his thoughts regarding the issue of slavery in the United States. Assign one of the following excerpts and accompanying questions for each student to read silently in groups of four to six, depending on the size of the class.

Note: All complete primary source material with student questions is available at this link.

Teacher Contextual Information for Primary Sources

Many instructors will have the contextual knowledge to briefly introduce each primary source reading to students, but this might not be the case with all six readings, particularly with Lincoln’s private correspondence. The annotations and sources below should be helpful as teacher background or, with high school students, possible in-depth or homework resources.

The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions: Address before the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, January 27, 1838

Context: On November 7, 1837, in Alton, Illinois, in what came to be a nationally publicized and polarizing event, a mob raided the warehouse where abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy stored his printing press, burned the building, and killed Lovejoy. Although the then-twenty-eight-year-old Lincoln did not mention Lovejoy by name, a major theme of Lincoln’s earliest published speech was the evil of mob rule and the need for respect for the law. For the complete speech and other background information, visit http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/lyceum-address-january-27-1838/.

Letter to Mary Speed, September 27, 1841

Context: In this letter to the half-sister of one of Lincoln’s best friends, Joshua Speed, Lincoln recounted his observations of a recent steamboat trip he and Speed took together. Parts of the letter would have outraged abolitionists because they hinted at Lincoln’s sympathy for slaves and their plight. Available at http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-mary-speed-september-27-1841/.

Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854

Context: Lincoln’s response to congressional passage of the highly divisive 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act allowing territories to exercise popular sovereignty regarding the question of whether or not to allow slavery marked the first time Lincoln made the moral evils of slavery and its threat to the republic a personal central political theme. For the complete speech and background information, visit http://ashbrook.org/library/document/speech-on-the-repeal-of-the-missouri-compromise/. Teachers might also want to read political scientist’s Kevin Portteus’s succinct essay on the historical significance of the speech at http://ashbrook.org/publications/onprin-feb2009-portteus/.

Letter to Joshua Speed, August 24, 1855

Context: This letter to a close friend, who as a Kentucky slaveholder had a different viewpoint on slavery than Lincoln, is influenced by Lincoln’s alarm concerning the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It also affords students the chance to read two different Lincoln accounts of the same steamboat journey and his reactions to the shackled slaves onboard. See the complete letter, which condemns not only slavery but also the anti-immigrant “Know-Nothing” Party, at

http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/speed.htm.

Dred Scott Decision Speech, Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857

Context: The Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case ruling against Scott—a slave who contended that because his master had moved him from a slave state to a free state and then a free territory, he was legally free on the grounds that slaves had no right to sue since blacks were not citizens, further divided an already-polarized union. Lincoln’s complete speech may be accessed at http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/speech-on-the-dred-scott-decision/.

First Debate with Stephen A. Douglas, Ottawa, Illinois, August 21, 1858

Context: U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and Lincoln's opponent for the Senate seat, engaged Lincoln in seven debates. (State legislatures elected U.S. senators until 1913, but the candidates held public debates to vie for support for the election from supportive legislators.) Much of the debates centered on issues such as slavery in the territories, the Dred Scott decision, and the morality of slavery. Although Douglas was reelected to the Senate, the debates propelled Lincoln and the antislavery Republican Party into the national spotlight. The transcript of the first debate with accompanying background information is available at https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/debate1.htm.

Author’s note: The excerpts from Lincoln’s letters are easier for students below eighth-grade reading levels if differentiation of reading skills is necessary.

Document Analysis Continued

After silent reading, have student complete the following for each excerpt:

Highlight at least five key words from each excerpt from Lincoln. These key words will help students write their summary “I think” statements.

Instruct students to answer questions that follow each excerpt to facilitate their summary statements and later discussion.

In order to summarize the selection, students should write an “I think” statement on their interpretation of Lincoln’s views from the assigned selection. (Example: “I think Lincoln is saying in this letter than slavery was wrong because it goes against their humanity.”)

Teacher should allow each student to share their “I think” statements within their groups.

Discussion (estimated time, thirty minutes)

Teacher should lead a whole-class discussion using the best of the “I think” statements and/or responses to text-based questions.

Culminating writing task (estimated time, thirty to sixty minutes)

Allow students to choose one of the following questions to respond to in writing. At this point, students will need all six documents for use as evidence.

Are there similarities and differences between Lincoln’s letters and his public speeches in regards to what he writes about slavery? Explain with evidence.

In what ways do you think Lincoln’s public addresses are influenced by the fact that he was a lawyer and aspired to be a democratically elected leader? Explain with evidence.

Use evidence from the primary sources presented in class to show that Lincoln was not an abolitionist.

Use evidence from the primary sources to show that Lincoln was against slavery.

In the nineteenth century, whether white Americans were for or against slavery, the vast majority of whites in the U.S. and Europe considered blacks an inferior race. Based on primary source evidence, how might Lincoln’s views on race conform to and contradict the dominant views of the majority race?

Editor’s note: Because of the contemporary sensitivity regarding the above topic, careful teacher preparation for this question is important. Two approaches are suggested: students should be introduced to the notion that historical thinking involves cultivating empathy (not sympathy) for people who lived in another era who held beliefs that today are considered “racist” or “backward.” A discussion making this point might be followed by a specific examination of Civil War-era beliefs about blacks. See the following website for accurate information on this topic: http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Freedmen/Intros/questions.html.

Assessment

Teachers should feel free to use a rubric of their choice to assess the writing task, or they may use the one below from the University of North Carolina School of Education:

References and Resources

https://youtu.be/rXdZe1Q-dQo: This brief video clip on YouTube of Lincoln’s early life from A&E network’s Biography series is titled “Lincoln: Growing Up on the Frontier.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8Ov1qS67v4: This is a longer, ninety-minute biography of Lincoln from the History Channel, available on YouTube.

http://tinyurl.com/y86ncut3: This daguerreotype of Congressman Abraham Lincoln was taken in 1846 by Nicholas H. Shepherd and is available on Wikimedia Commons.

http://tinyurl.com/y74mhpco: This photograph of the Lincoln Memorial by Attilio Piccirilli for Daniel Chester French (1920) is available on Wikimedia Commons.

http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/: Lincoln’s 1838 Lyceum Speech and his letter to Mary Speed, from The House Divided Project: Lincoln's Writings, The Multi-Media Edition by Dickinson College, are available at this URL.

http://ashbrook.org/: Lincoln’s 1854 Peoria Speech, accompanying materials, and Lincoln’s 1857 Dred Scott Speech are available at this URL from the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University.

https://www.c-span.org/series/?LincolnDouglas: This site has the "Lincoln-Douglas Debates" from C-Span Classroom, a series of reenactments in 1994 of the Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas Illinois senatorial debates in 1858.

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/lincoln/essays/lincoln-and-abolitionism#fn2: This site has an essay titled “Lincoln and Abolitionism” by Douglas L. Wilson from The Gilder Lehrman Institute and is included as a teacher background.

https://vimeo.com/69675871: Matthew Pinsker of Dickinson College’s lecture “Understanding Lincoln: Lyceum Address (1838)” from The Gilder Lehrman Institute is available here.

http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/speeches.htm: Lincoln’s 1855 Letter to Joshua Speed is available at the Abraham Lincoln Online website.

http://www.nps.gov: The transcript of Lincoln’s August 21, 1858, first debate with Stephen A. Douglas and accompanying materials are available at the National Park Service website.