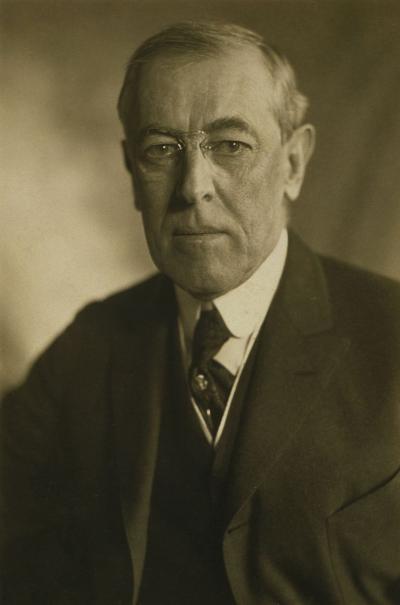

Executive Decision-Making during Times of Crisis: Woodrow Wilson and World War I

This complete module with all materials may be downloaded as a PDF here.

Linda Moss Mines

Girls Preparatory School

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Woodrow Wilson. Source: Wikipedia at https://tinyurl.com/yaxtcdcj

This module was developed and utilized for an eleventh and twelfth-grade advanced placement United States government class to address the AP syllabus topic "Presidential Powers." However, the module could easily be adapted for use in a standard or AP United States history class, a world history class, a twentieth-century U.S. foreign policy class, or a number of other elective semester courses offered at the high school level.

Estimated module length: Four forty-five minute classes, or a total of three hours

Background Information

When the assassination of Austria-Hungary’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand occurred in 1914 and triggered the implementation of a previously negotiated series of mutual support alliances among the European nations, President Woodrow Wilson, who believed in American neutrality, saw the U.S. role as the "peace broker." The 1914–1918 Great War (known today as World War I) developed into a war unlike any the belligerent nations had ever experienced, and Europe became a horrific battlefield. While the United States philosophically and fiscally supported the Triple Entente in the beginning years of the conflict, Wilson was determined to keep the nation out of armed conflict. However, by 1917, it looked as though both Russia and France would pull out of the war, leaving Great Britain alone to withstand the onslaught of German forces and a possible German victory. That outcome was simply not acceptable to Wilson.

This module is designed to introduce students to the series of events that precipitated the U.S. entry into World War I and the steps by which Wilson moved his perception of America’s role from "peace broker" to "war ally." The process used in this module can be applied to other executive decision-making scenarios as varied as Truman’s decision to remove General Douglas MacArthur from command during the Korean Conflict to President George W. Bush’s decision to announce a war against terrorism.

Objectives

Students will:

Identify the most significant military actions of 1914–1917, leading to the attrition among Allied forces and the expansion of aggressive actions toward the United States.

Analyze these situations and explore what alternative actions might have been considered by Wilson and his chief advisers.

Explain the significance of unrestrictive submarine warfare, the Zimmerman telegram, the belligerent communications from Germany, and the numerous sinking of ships in driving the United States toward a declaration of war, and Wilson’s choice of language for the "Proclamation of War."

Analyze and critique excerpts from Wilson’s April 3, 1917, Congressional War Message.

Identify key opposition to the war and the Wilson administration’s reactions by applying analytical skills to understand significant events such as Schenck v. United States, Eugene Debs's speeches, and other writings.

Prerequisite Knowledge

This module was designed to assist students in moving from a broad perception of the role of the president in the decision-making process to a view grounded in experience with actual events and the connecting subsequent presidential actions. The assumption is that students will possess only general knowledge related to World War I and very little specific content knowledge.

Module, day one: Why We Fight

As students enter the classroom, each will be given a sheet of paper upon which the following is written:

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” Sun Tzu

“War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend.” J. R. R. Tolkien

Questions for students:

While war is never desired, throughout history, humans have engaged in armed conflict because they believed they were fighting for a purpose and to preserve a way of life. As we begin to analyze World War I and Wilson’s decision to bring the United States into the conflict in order to “make the world safe for democracy,” it is important that we understand his particular perception of the American legacy as the “shining city on a hill.”

In your own words, what did Wilson mean when he used the phrase, “make the world safe for democracy?”

After fifteen-twenty minutes, students will be asked to form groups of four and "round-robin" answers, adding descriptors to their own list of phrases. After five minutes, a spokesperson from each group will share with the class.

After the brief discussion, instructors might ask these two questions:

For many people, the idea of war is unsettling, and diplomacy is offered as an alternative to combat. Unfortunately, diplomacy often works only among honorable people. How might you deal with the "dishonorable" leader? Does evil exist?

If evil exists and there are some ideals worth fighting to preserve, what would you be willing to fight for as an individual or as part of a group?

Teachers should encourage students to discuss the questions (estimated time, ten to fifteen minutes).

Module, day two: World War I Prior to 1917

Pose this question and allow time for brief discussion: Why did war break out in Europe in 1914? (estimated time, two to three minutes)

To further answer this question, divide the class into six groups, with each assigned one of six causes that together can be recalled as MAIMIN:

Group 1: Militarism and military plans

Group 2: Alliance system

Group 3: Imperialism

Group 4: Mass politics

Group 5: Intellectual content

Group 6: Nationalism

Students use their text, internet, and other sources to create a general summary of their category (estimated time, fifteen minutes).

Each group (utilizing a spokesperson) is given three minutes to summarize the significance of their cause on the outbreak of war.

Have students view the eight-minute video clip at http://youtu.be/ZmHxq28440c, which explains the significance of the assassination of Ferdinand.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Source: Wikipedia at https://tinyurl.com/hy2r2jh.

Debriefing questions:

How did the heir to the throne of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire view the Serbians? The Slavs?

What was the significance of the Black Hand?

What was the reaction of the Serbians to Ferdinandâs visit?

Note: The ensuing primary source excerpts and background reading assignments can be downloaded at this link.

Students then read the German Proclamations of War against Russia and France and identify Germanyâs justification for war (primary source document Nos. 1 and 2). A brief discussion of these documents will conclude activities for the day.

Homework for day three:

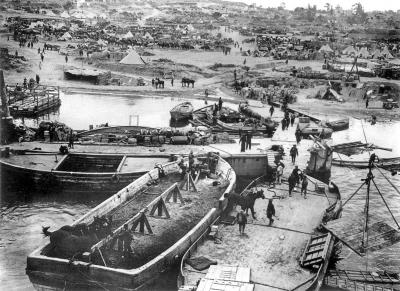

V Beach at Cape Helles, Gallipoli, May 6, 1915. View is from the bow of the collier SS River Clyde. Taken by Photographer Lt. Wilfred Park RNVR (Photographic Section) accompanying 3rd WR Royal Navy Thomas McNamee. Source: Wikipedia at https://tinyurl.com/y8u88uvc.

Reading assignment: Background document No. 3, "Who Declared War and When," and background document, No. 4, "Significant Battles of the First World War: 1914–1916." Indicate to students they should be prepared to discuss these questions during the next class.

Were you surprised to see some of the nations listed as either "Allies” or "Central Powers”? Why might they choose to join in this conflict?

Based on these brief summaries of the six most significant early battles of World War I, how were the Allied forces (Great Britain, France, and Russia) faring? If casualty rates can be used as a part of that analysis, what are your thoughts?

How different were the techniques used during World War I from those of earlier conflicts in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

What might you predict as an outcome of the war based only on the early battles?

Module day three: Wilson and World War I: Making "the World Safe for Democracy”

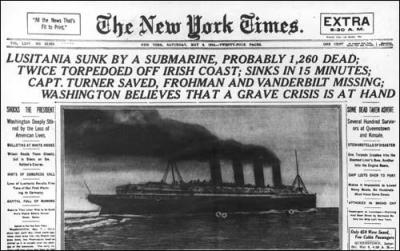

The New York Times front-page story of the sinking of the Lusitania. Source: Spartacus Educational at https://tinyurl.com/yd7tpuym.

Make an opening commentary similar to what follows: Weâve spent the last two days examining the causes and several of the actions of World War I. You may have noticed that while Cuba and Haiti joined the Allied forces, the United States had chosen to remain neutral, although the nation did support Great Britain and France through the selling of arms and munitions. However, by 1917, Wilson, who had deliberately kept the U.S. neutral, felt compelled to ask the U.S. Congress for a "Proclamation of War." Today, weâre going to examine the âwhysâ of Wilsonâs decision to enter the war on the side of the Triple Entente.

Distribute or have students access three handouts: background reading and video No. 5: âThe Sinking of the Lusitaniaâ; primary source document No. 6: âThe Zimmerman Telegramâ; and background reading No. 7: âUnrestricted Submarine Warfare.â

Ask students to read the short background information and view "The Sinking of the Lusitania" (estimated time, four to five minutes).

Discuss the following questions:

How did the citizens of the U.S. react to the news of the Lusitania?

How did the German action conflict with U.S. values?

Have students read the Zimmerman telegram (estimated time, five to ten minutes).

Discuss the following questions:

What kind of deal was the German government attempting to negotiate with Mexico?

What did the German government hope Japan, allied with the Triple Entente against the Central Powers, would do to further Germanyâs and possibly Mexicoâs interests?

Students are asked to read "Unrestricted Submarine Warfareâ (estimated time, five to seven minutes).

Discuss the following questions:

How does this article relate to our earlier discussion of the Lusitania?

Following the sinking of the Lusitania and the international outcry, Germany pulled back its U-2s and pledged to allow passenger liners free navigation of the waters. If Germany knew that returning to submarine warfare would anger the U.S. and Germany did not want the U.S. entering the Great War, why would they return to this policy?

Students should, through analysis of the Zimmerman telegram and the contextual background reading on Germanyâs 1917 Unrestricted Submarine Warfare Policy, understand two critical events that caused the U.S. to enter World War I, effective April 6, 1917. Students, because of possible confusion caused by the fact that Japan would instigate World War II twenty-four years later with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, should be reminded that when learning about the Zimmerman telegram, the Japanese government pointedly repudiated Germany.

Other events that caused America to eventually enter the war were, despite having a significant number of German-American citizens and immigrants, the cultural and political affinity felt by many Americans for the British and French due to the common language shared by the U.S. and most of the U.K., and liberal democratic traditions all three nations shared. Although in the beginning of the war American business traded with both sides, the British blockade quickly caused a 90 percent drop in U.S.-German trade. U.S. private companies supplied their British and French allies with a vast array of goods both before and after the U.S. entered World War I.

Analyzing Wilsonâs War Message

Have students digitally access or distribute primary source document and reading No. 8, "Excerpts: Woodrow Wilsonâs War Message to Congress, April 2nd, 1917 and Historiansâ Reactions to Woodrow Wilsonâs War Message."

Students should then read the three excerpts of Wilsonâs War Message and answer all questions. The instructor should then conduct a whole-class discussion on the student answers. Instructors might want to read the speech in its entirety in Appendix 2 (http://tinyurl.com/y8jc22x4) before class so as to briefly reiterate the specific causes of Americaâs entry into war that students have already considered (estimated time, twenty minutes).

Questions for excerpt 1

What is an autocratic government? Is Wilson asking Congress to declare war on all autocratic governments worldwide?

Is Wilson asking the U.S. to fight for the freedom of all of the worldâs people? Was/is such an effort possible?

Questions for excerpt 2

Has a nation in world history ever successfully won a war that resulted in world peace? Defend your answer with evidence if possible.

Interpret what you think Wilson specifically meant in his sentence, âThe world must be made safe for democracy.â

Questions for excerpt 3

Is it possible for any nation to achieve all the above objectives in one war? Defend your answer with evidence.

Should the U.S. make war until all nations are democracies? Why or why not?

Historiansâ Reactions to Woodrow Wilsonâs War Message

Introduce the critique of Wilsonâs speech by informing students that a number of historians think the speech set dangerous precedents in the U.S. that negatively impacted U.S. and world history. This perspective is shared by some historians who favored Americaâs entry into World War I but not some of the broader goals Wilson used to justify the address.

Have students read the excerpt in primary source document and reading No. 8 from Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Walter McDougall (https://www.fpri.org/?p=14654 ).

Discuss the following questions:

In your own words, explain what you think the differences were in the three choices McDougall asserts Wilson could have made.

What does McDougall mean when he argues, âWilson declared America the worldâs messiahâ? Should the U.S. be the worldâs messiah? Why or why not?

Homework for day four:

Instructors should introduce homework by making these or similar comments: Although Congress overwhelmingly supported Wilsonâs request for a declaration of war, not all U.S. citizens agreed with their nationâs direct involvement in World War I. Tonight, you will spend some time acquainting yourself with the opposing viewpoints and the federal governmentâs reaction to dissent at home.

Visit http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/capitalism/landmark_schenck.html and read the summary provided for Schenck .v United States. Now visit https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/249us47 and read this brief summary.

Eugene Debs was undoubtedly the most vocal opponent of the U.S. involvement in World War I and ultimately was sentenced to prison for statements made during a speech in Canton, Ohio. A frequent candidate for president, Debs based his opposition on his Socialist ideology. Debsâs imprisonment was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. To understand more about his opposition to the war and his imprisonment, visit http://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/Eugene_Debs.

Be prepared to discuss the Schenck and Debs cases.

Module, day four: Domestic Dissent against World War I and General Reflections on Wilsonâs Decision

Class begins with a discussion of the courtâs distinction in Schenck between "free speech" and "free speech during time of war."

Discuss the following questions:

Why might the court have reacted to Schenckâs actions as it did?

What are the critical lines in the decision? Debs's speech in Canton occurred in 1918, after the U.S. was already involved in the war. Does that timing have any impact on the courtâs decision? How might the general public and the governmentâs reaction to his speech been impacted by events occurring in other nations? Does our freedom of speech guarantee individuals a right to "petition" for grievances? Assemble in opposition? Under what conditions?

Teachers might also consider having students do a summary writing exercise and ensuing discussion.

You have now examined the historical record of controversial issues related to U.S. involvement in World War I. In 200 words, assess the validity of this statement: The United States had ample reasons for entering the Great War in 1917, and the fight to "make the world safe for democracy" was a continuation of our quest to bring liberty, equality, and justice to the world (estimated time, twenty minutes).

Students speak based on their short free-response essays, and the instructor assists students to reflect upon their thoughts through a discussion involving a reexamination of the introduction to the Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution, and the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights.

Final module questions:

How difficult must it have been for Wilson to move beyond his background as a historian and university president to making a decision that would directly impact the lives of two million U.S. armed forces members?

Letâs circle back to our original question: Are there values still worth fighting for when diplomacy fails?

How difficult is that decision for a president? How might the public be encouraged to engage in civil discourse about political and military courses of action?

Enrichment/Alternative Activities

Editorâs Note: World War I

Instructors may wish to share this document (also below) with students and ask them to reflect on what points that follow probably apply to most wars, what points are specifically applicable to World War I, and how World War I helped change the course of American and world history.

Ten Points for Reflection: The U.S. and World War I

-

Although American deaths in World War I pale in significance to allies, opponents, and a substantial number of U.S. military personnel that died from disease, the 116,516 U.S. soldiers who died make the war the third leading costly war involving loss of American lives in U.S. history. Only the American Civil War (Confederate and Union deaths combined) and World War II rank higher (Department of Defense). American forces were instrumental in turning the tide of the war as Germany and its allies were defeated. However, World War I did not succeed in making the world safe for democracy: Germany and the Western Powers were at war again twenty years later.

-

World War I helped spawn the growth of Fascism and Communism in Europe, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of millions of people. In contrast to the former destructive belief systems, Wilsonâs liberal internationalism committed future U.S. presidents in words and sometimes actions to global promotion of democracy, capitalism, and freedom. This U.S. stance has been evidentially liberating for a massive amount of people globally but has caused unintended domestic and foreign negative consequences as well.

-

World War I was the first conflict where a president orchestrated a massive national government propaganda campaign using mass media, such as more effective print technology and movies previously unavailable. Wilson created the Federal Committee on Public Information that recruited 75,000 speakers (âFour Minute Menâ) to give short war aims talks in theater intermissions and other similar events, and printed 100 million pamphlets in several languages, as well as promoted movies supporting the war.

-

Once the U.S. was in the war, the event created some government-initiated, and private discrimination against German-Americans, then and now, the largest ethnic group in the U.S.* âHamburgerâ was replaced by âliberty sandwichâ and sauerkraut was replaced by âliberty cabbage.â Public schools in German-American-dominated cities like St. Louis, Missouri, had to stop using German as their primary language, and many German-American families changed their names from German to English.

-

World War I was by far the most expensive conflict in American history at the time. World War I cost the federal government ten times more than the Civil War. Americans, because of World War I, faced much higher federal taxes than any time since the Internal Revenue was created during the Civil War.

-

Although both because of the relatively short time the U.S. was in the war, and strong cultural pro-freedom attitudes, the federal government cajoled and persuaded citizens, rather than commanded them, to make economic sacrifices and mobilize for various war efforts. Federal Food Commissioner Herbert Hoover exhorted housewives to be patriotic and observe âMeatless Mondays" and âWheatless Wednesdays,â and Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo sponsored massive rallies to promote the purchase of war bonds. Nevertheless, the Wilson administration took over the railroads in late 1917 so precedents were set regarding central government control of the economy that would be expanded during World War II.

-

The federal government initially had relatively low numbers of volunteers for World War I. The Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, enabled the size of the American army to increase from 200,000 in May 1917 to nearly four million by warâs end in 1918. About two million Americans served overseas.

-

Government also, through the 1917 Espionage Act and the 1918 Sedition Act, was able to prosecute pacifists, left-wing political groups, and unions that opposed the war.

-

World War I planted the seeds for improvement in the lives of women and African-Americans in that industrial jobs opened to these groups because of a shortage of manpower due to the war. Although these gains were short-lived when returning soldiers reclaimed jobs, the precedent was set for future social change.

-

New technology often emerges as a result of war. In addition to new military technology such as the tank, examples of World War I technology that now have widespread use include the zipper, the wristwatch, radio communications technology, daylight saving time, stainless steel, sun lamps, and tea bags.

Sources for this extension:

Evans, Stephen. â10 Inventions That Owe Their Success to World War One.â BBC. April 13, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26935867

Foner, Eric, and John A. Garraty. The Readerâs Companion to American History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Johnson,Paul. A History of the American People. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

Neiberg, Michael. âWhat Students Need to Know about WWI.â Foreign Policy Research Institute. August 29, 2008. http://www.fpri.org/article/2008/08/what-students-need-to-know-about-wwi/

Norman, Geoffrey. âWoodrow Wilsonâs War.â The Weekly Standard. April 3, 2017.

Editorâs Note:

Literature, America, and World War I: Willa Cather

Often, reading good literature offers deeper insights at many levels about understanding human feelings, action, and interactions than focusing exclusively on the study of more objective subjects such as political science, history, and economics. Although European authors in several nations produced an impressive body of fiction, poetry, and essays on the war, this was less true in the case of American authors.

Willa Cather is a memorable exception. A native Midwesterner who spent considerable time both in New York City and her home state of Nebraska during the war, Cather penned an essay titled âRoll Call on the Prairiesâ in The Red Cross Magazine (July 1919) that is available at the link below:

http://cather.unl.edu/nf007.html.

The short, well-written essay is a gem for students since it contrasts the markedly different levels of enthusiasm for the war exhibited by what pundits might label today as âRed Statesâ and âBlue States.â

Cather also won a 1923 Pulitzer Prize for her superb World War I novel, One of Ours (1922). Cather tells the story of Nebraskan Claude Wheeler, who felt trapped by family and fate that the young, intelligent, and educated man considered boring and mind-numbing. World War I gave Claude a cause greater than himself, and his life changed forever because of the war. The novel also illustrates the ethnic conflicts between Anglo-Nebraskans and their Central European neighbors that intensely escalated as the war progressed, especially after the U.S. entered the conflict. The 337-page book is inexpensive and available at http://amzn.com/143828456X.

References and Resources

http://youtu.be/ZmHxq28440c: âA Shot that Changed the WorldâThe Assassination of Franz Ferdinandâ is an eight-minute segment on Franz Ferdinandâs assassination by The Great War Project on YouTube.

https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/lusitania This History.com three minute video provides primary source footage of this important event.

http://tinyurl.com/y8jc22x4: This is a link to Woodrow Wilsonâs War Message to Congress in 1917.

https://www.fpri.org/?p=14654: This is a link to Walter A. McDougallâs article âThe Great Warâs Impact on American Foreign Policy and Civic Religionâ for the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/capitalism/landmark_schenck.html: This is a short essay on Schenck v. U.S. by Alex McBride for the "Capitalism and Conflict" section of The Supreme Court Series by PBS for Classrooms.

https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/249us47: This is a brief overview of Schenck v. United States from the website Oyez.

http://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/Eugene_Debs: This is the entry on Eugene Debs from the International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-woodrow-wilsons-war-speech-congress-changed-him-and-nation-180962755/ This Smithsonian.com by journalist Eric Trickey that appeared on April 3rd 2017 offers an accessible story of the politics and repercussions of Wilsonâs change to war president.

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=65366: This is Wilsonâs request for war against Germany.

Source for Germanyâs declarations of war: Horne, Charles F. Source Records of the Great War. Vol. 2. New York: National Alumni, 1923.

Source for âWho Declared War and Whenâ: Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia. Vol. 27, 1983.

Excerpts from â10 Significant Battles of the First World Warâ: http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/10-significant-battles-of-the-first-world-war

Transcript of the Zimmerman telegram: https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/The_Zimmerman_Note

Background for the Zimmerman telegram: Alexander, Mary, and Marilyn Childress. "The Zimmerman Telegram." Social Education 45, no. 4 (1981): 266.

Source for âUnrestricted Submarine Warfareâ primary source document: www.historylearningsite.co.uk.